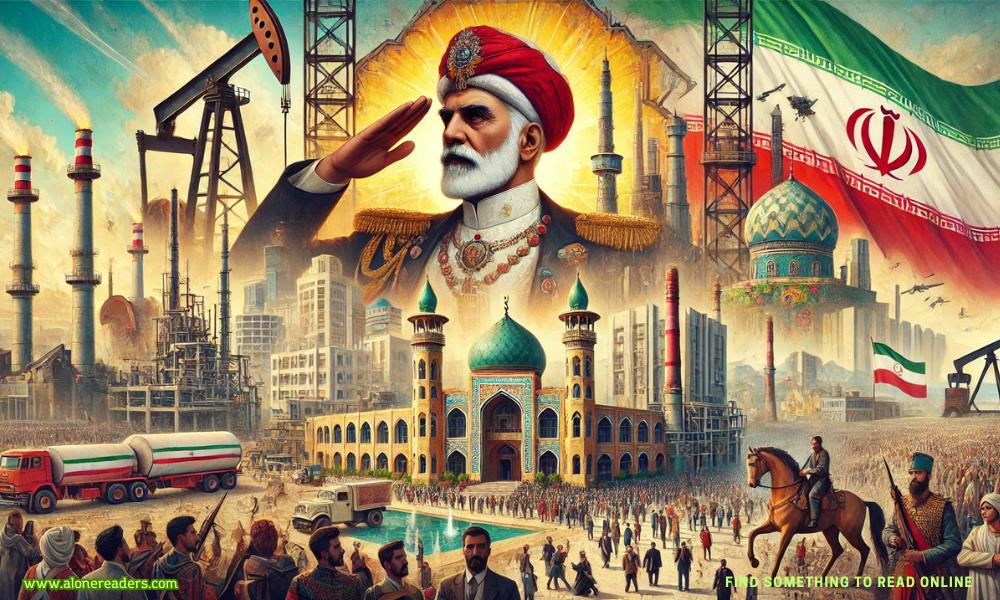

The White Revolution, launched in 1963 by Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, marked a transformative period in Iran's history. With a sweeping series of reforms, the Shah aimed to modernize the country and consolidate his power. These changes, however, sparked fierce opposition from religious leaders and segments of the Iranian populace, ultimately setting the stage for the Islamic Revolution of 1979.

This article delves into the key components of the White Revolution, the modernization efforts, and the significant religious and political backlash it incited.

The term "White Revolution" symbolized a peaceful transformation as opposed to a violent upheaval. By the early 1960s, Iran was at a crossroads: it was rich in oil resources but faced social and economic inequalities. The Shah, backed by the United States, sought to bolster his regime through rapid modernization and reform while curbing the influence of the clergy and traditional elite.

The plan included six key reforms, later expanded to a dozen, targeting land distribution, women’s rights, education, and industrial growth. These initiatives were designed to gain support from rural populations and the emerging middle class while undermining the clergy’s hold on Iranian society.

Land Reform

One of the cornerstone policies of the White Revolution was land redistribution. The Shah sought to weaken the feudal land-owning class by redistributing land to tenant farmers. The program aimed to improve agricultural productivity and reduce rural poverty, but its implementation was flawed. While some farmers benefited, many received plots too small to sustain their livelihoods, leading to urban migration and further socio-economic challenges.

Women’s Rights

The Shah introduced reforms to improve the status of women, including granting them the right to vote and participate in elections. Family laws were revised to increase women’s rights in marriage and divorce. These measures angered conservative religious factions, who saw them as an affront to Islamic values.

Education and Literacy

The Literacy Corps, a flagship program of the White Revolution, sent young educated Iranians to rural areas to teach reading and writing. This initiative was aimed at reducing illiteracy rates and spreading the Shah's modernization message to remote regions.

Nationalization of Forests and Pastures

The Shah sought to preserve Iran's natural resources by nationalizing forests and pastures. While this reform was less controversial, it underscored his desire to centralize control over the country’s assets.

Industrial Growth and Profit-Sharing

To stimulate industrial development, the Shah encouraged profit-sharing schemes in private companies, giving workers a stake in corporate earnings. This was intended to foster loyalty among the working class.

Health and Infrastructure

Investments in healthcare and infrastructure projects were also significant. New hospitals, clinics, and rural health centers aimed to improve public health, while roads, dams, and irrigation systems modernized the nation’s physical infrastructure.

Despite its ambitious goals, the White Revolution faced intense resistance, particularly from the clergy. The ulama (religious scholars) viewed the reforms as an attack on Islamic traditions and their influence. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini emerged as a vocal critic, condemning the Shah’s policies as anti-Islamic and subservient to Western interests.

The Role of the Clergy

The clergy’s opposition centered on land reforms that stripped religious endowments (waqf) of their properties and women’s rights reforms, which they perceived as undermining Islamic family values. These changes disrupted the traditional power structures that had allowed the clergy to maintain socio-political authority.

Urban Migration and Social Displacement

The land reforms inadvertently contributed to widespread rural-urban migration. Many small farmers, unable to sustain themselves on redistributed plots, moved to cities in search of work, exacerbating social inequalities and fostering discontent among the urban poor.

Westernization and Identity Crisis

The Shah’s emphasis on Western-style modernization alienated segments of Iranian society who felt their cultural and religious identity was under siege. His close alliance with the United States further fueled accusations that he was a puppet of foreign powers.

The White Revolution’s legacy is complex. On one hand, it succeeded in laying the groundwork for industrial and infrastructural development. The reforms also contributed to some progress in literacy and women’s rights. On the other hand, its failures—poor implementation, uneven benefits, and disregard for traditional structures—exacerbated social tensions.

The backlash from religious leaders like Ayatollah Khomeini and their ability to mobilize discontented masses foreshadowed the eventual downfall of the Shah. The White Revolution, while intended to secure the monarchy, ironically hastened its collapse. By alienating powerful religious factions and failing to address widespread socio-economic grievances, it paved the way for the Islamic Revolution of 1979.

Conclusion

The White Revolution of 1963 was a pivotal moment in Iran’s history. It symbolized the Shah’s ambitious vision for a modernized and secular Iran but also highlighted the deep-rooted divisions within Iranian society. The resistance it provoked from the clergy and other groups underscored the challenges of implementing rapid reforms in a traditional society.

Today, the White Revolution serves as a cautionary tale about the complexities of modernization, the importance of inclusivity in reform, and the enduring power of religious and cultural identities in shaping national trajectories.