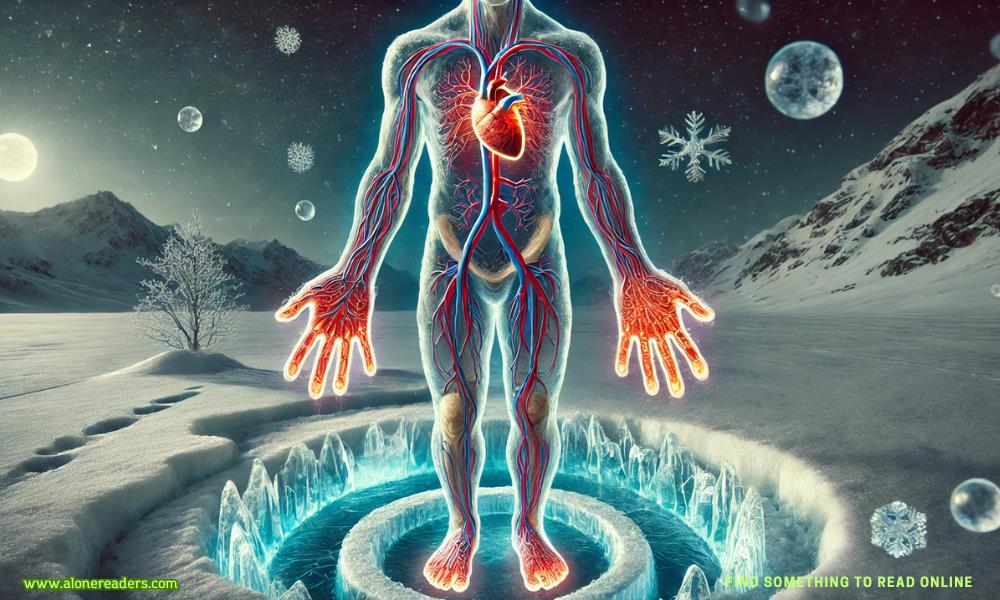

When you step outside on a chilly morning or find yourself in a cold environment, you might notice that your hands and feet begin to feel cold long before the rest of your body does. This common phenomenon is not merely an inconvenience or a quirk of nature—it is a finely tuned survival mechanism that has evolved to protect our vital organs. The body’s response to cold exposure is complex and fascinating, involving a process known as vasoconstriction, where blood vessels in the extremities constrict to reduce blood flow. By doing so, the body diverts warm blood away from the periphery and toward the core, ensuring that the heart, lungs, brain, and other critical organs remain at a stable and safe temperature.

This natural defense mechanism is essential because maintaining the temperature of vital organs is crucial for survival. The body’s core temperature needs to be kept within a narrow range for metabolic processes to occur optimally. When exposed to cold conditions, the body makes a rapid assessment of the risk to these central systems. In response, it prioritizes core warmth over the comfort of the hands, feet, and other peripheral regions. As a result, the blood vessels in these areas constrict, reducing blood flow and thereby limiting the amount of heat lost to the environment. This process is an integral part of thermoregulation and is particularly important in preventing hypothermia.

The phenomenon of cold hands and feet is not unique to humans; it can be observed across many warm-blooded animals. In the wild, where sudden drops in temperature can occur, this mechanism serves to protect the animal's life-sustaining organs. By limiting blood flow to the limbs, the animal conserves energy and maintains the warmth of its core. For humans, however, this can often lead to discomfort, numbness, or even pain in the extremities, especially if the cold exposure is prolonged or intense.

The underlying physiology behind this process involves several interconnected systems within the body. When the skin detects a drop in temperature, sensory receptors send signals to the brain, which then activates the sympathetic nervous system. This activation triggers the release of adrenaline and other stress hormones, which, among other effects, cause the smooth muscles in the walls of blood vessels to contract. The resulting vasoconstriction is most pronounced in the peripheral regions where blood vessels are smaller and more susceptible to narrowing. While this response is beneficial in the short term, it can have side effects if the extremities remain cold for extended periods.

Over time, repeated exposure to cold conditions and the resulting vasoconstriction can lead to adaptations in the circulatory system. In some individuals, this may result in chronic conditions such as Raynaud’s phenomenon, where blood flow to the fingers and toes is excessively reduced in response to cold or stress. In Raynaud’s, the affected areas can turn white or blue and become numb or painful. Although this condition is usually not life-threatening, it underscores the delicate balance the body must maintain between protecting vital organs and ensuring adequate circulation to all tissues.

Another important aspect to consider is the role of insulation, both natural and artificial, in mitigating the effects of cold exposure. When we dress warmly or use protective gear, we help the body maintain its core temperature without having to rely as heavily on vasoconstriction. Clothing acts as an external barrier to heat loss, reducing the need for the body to divert blood away from the extremities. This is why appropriate attire in cold weather is not just a matter of comfort but also an essential part of maintaining overall health and preventing conditions like frostbite or hypothermia.

The impact of cold on the extremities also has implications for various aspects of daily life and occupational health. For individuals who work outdoors in cold climates, managing the balance between core warmth and peripheral comfort is a daily challenge. Workers may use heated gloves, insulated boots, and other specialized equipment to maintain blood flow and prevent the discomfort and potential injury associated with prolonged exposure to cold. In addition, athletes who train in cold weather must be particularly mindful of how their bodies respond to the cold, as reduced blood flow to the limbs can affect performance and increase the risk of muscle injuries.

On a more microscopic level, the body’s response to cold exposure involves the regulation of a hormone called norepinephrine, which plays a significant role in the process of vasoconstriction. Norepinephrine is released by nerve endings in the vascular smooth muscle, causing the blood vessels to narrow. This response is both rapid and reversible, allowing the body to adjust quickly to changes in external temperature. However, the efficiency of this mechanism can vary from person to person, influenced by factors such as age, overall health, and even genetics. Some individuals may naturally have a more robust vasoconstrictive response, which, while protective of the core, might lead to chronic issues with cold extremities.

Nutrition and overall fitness also contribute to how well the body manages cold exposure. Adequate levels of certain vitamins and minerals, particularly those that support healthy blood circulation, can improve the body’s ability to maintain warmth in all areas. For example, omega-3 fatty acids, found in foods like fish and walnuts, have been shown to support cardiovascular health and may enhance blood flow to the extremities. Likewise, regular physical activity improves circulation, helping to counteract some of the effects of vasoconstriction during cold exposure. Engaging in moderate exercise can stimulate blood flow and generate internal heat, reducing the stark temperature difference between the core and the limbs.

While the physiological response to cold is automatic and largely beneficial, there are ways to manage and mitigate its more uncomfortable aspects. One common approach is to gradually acclimate the body to cold environments. Regular, controlled exposure to lower temperatures can help the body adapt over time, improving circulation and reducing the severity of vasoconstriction. Techniques such as contrast bathing, where one alternates between warm and cold water, are sometimes used in therapeutic settings to enhance blood flow and reduce discomfort in the extremities.

In addition to acclimation strategies, various lifestyle adjustments can also be helpful. Keeping the body well-hydrated and nourished supports overall metabolic function and ensures that the circulatory system remains as efficient as possible. Stress management is another important factor, as heightened stress levels can exacerbate the body’s vasoconstrictive response. Practices such as deep breathing, meditation, and yoga may help in reducing stress-induced constriction of blood vessels, thereby promoting better overall circulation.

It is also worth noting that the body’s prioritization of core warmth has implications for medical conditions beyond simple discomfort. In cases of severe hypothermia, for example, the body’s natural response to preserve core temperature becomes a critical factor in survival. Medical professionals must understand the nuances of this response when treating patients exposed to extreme cold. Rewarming strategies in hypothermic patients are carefully designed to avoid sudden changes in blood flow that might lead to complications. Gradual rewarming is key, ensuring that the blood vessels in the extremities relax slowly and that blood flow resumes in a controlled manner.

Despite its protective advantages, the natural tendency for the body to let the extremities get colder can sometimes be misunderstood. Many people mistakenly believe that cold hands and feet are merely a sign of poor circulation or an underlying health problem, when in fact, it is often a normal and healthy response to cold exposure. Awareness of this process can help reduce unnecessary worry and encourage individuals to take appropriate measures, such as dressing warmly and avoiding prolonged exposure to cold environments.

In summary, the phenomenon of cold hands and feet is a sophisticated biological response that plays a critical role in our survival. By constricting blood vessels in the extremities, the body ensures that vital organs remain warm and functional even in harsh conditions. This mechanism, while sometimes uncomfortable, is an essential part of thermoregulation and reflects the body’s remarkable ability to adapt to its environment. Understanding the science behind this process not only provides insight into our evolutionary past but also underscores the importance of taking proactive steps to protect our health in cold weather. Through proper clothing, gradual acclimation, and lifestyle adjustments, we can support our body’s natural defenses while minimizing the discomfort of cold extremities.