The My Lai Massacre remains one of the most harrowing episodes of the Vietnam War, an event that symbolizes the tragic consequences of warfare both for civilians and the soldiers involved. Occurring on March 16, 1968, in the Son My village of South Vietnam—though commonly referred to as My Lai due to the largest hamlet in the area—this atrocity involved a company of U.S. Army soldiers who were ordered to search for enemy combatants but ended up slaughtering hundreds of unarmed civilians. For many, the name “My Lai” has become synonymous with the moral injuries and psychological scarring that can result from combat situations where the lines between friend and foe are blurred. The massacre was not only a military tragedy but also a moral calamity that rattled global perceptions of the war and ignited fervent debates about the American military’s role in Vietnam.

The context of the My Lai Massacre was shaped by the chaotic environment of the Vietnam War. By 1968, the conflict had already escalated, with American forces deeply entangled and public support back home beginning to crack under the weight of mounting casualties and televised brutality. U.S. soldiers serving in Vietnam often found themselves in unfamiliar territory, patrolling hostile regions where the enemy was not always easy to identify. The Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army fighters frequently blended in with local populations, forcing American troops to remain constantly vigilant. This tense and disorienting atmosphere could intensify fear, paranoia, and frustration. In the lead-up to My Lai, some units had suffered significant casualties from booby traps, snipers, and ambushes, leaving them emotionally strained and often eager for retribution. These factors laid the groundwork for the tragic events that would soon unfold.

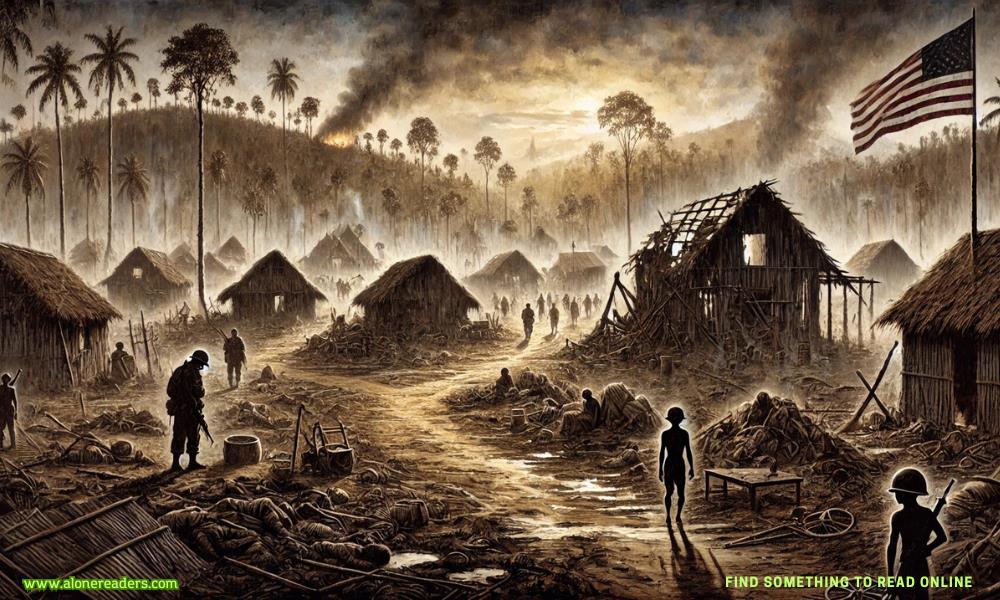

On the morning of March 16, 1968, the U.S. Army’s Charlie Company, 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment, under the command of Lieutenant William Calley and Captain Ernest Medina, was helicoptered into the vicinity of My Lai. The soldiers were briefed that the village harbored Viet Cong fighters, and they were tasked with eliminating any possible threat. They anticipated armed resistance, but upon arrival, they encountered primarily women, children, and the elderly—unarmed civilians. Despite the lack of armed opposition, the soldiers proceeded to shoot at villagers indiscriminately and set fire to huts. Survivors’ accounts describe scenes of unimaginable horror: families forced into ditches and executed at point-blank range, screams echoing amid the gunfire. It is estimated that between 300 and 500 unarmed Vietnamese were killed that day, although the exact number is still debated.

In the immediate aftermath, the soldiers filed reports indicating a successful operation against Viet Cong forces, claiming they had killed a large number of enemy combatants. Initially, the official narrative of My Lai was hidden from the public, as the commanding officers and various authorities worked to suppress or distort the facts. Soldiers who participated or witnessed atrocities were instructed to remain silent or risk punishment. A few individuals, however, found the strength and moral courage to speak up. One of the most notable figures was Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson Jr., a helicopter pilot who intervened during the massacre, placing himself and his crew in harm’s way to rescue civilians. Thompson reported the incident to his superiors, though his statements were at first dismissed or ignored.

It was not until investigative journalist Seymour Hersh broke the story in November 1969 that the broader American public learned of the atrocities committed at My Lai. Graphic photographs taken by U.S. Army photographer Ron Haeberle provided visceral proof of the killings, galvanizing anti-war sentiment and sparking international outrage. As the images were published in newspapers and magazines, public support for the conflict in Vietnam eroded further. The notion that American soldiers could commit such crimes shocked many citizens who had held onto ideals of heroic patriotism and believed the United States intervened in Vietnam to protect freedom and democracy. My Lai became a watershed moment in the ongoing national conversation about the morality and justifiability of the war.

Legal repercussions from the massacre were tangled and complex. Lieutenant William Calley was the only individual convicted for his involvement, found guilty of killing 22 unarmed Vietnamese civilians. Initially sentenced to life in prison, he served a brief period of house arrest after President Richard Nixon intervened, reducing his sentence. This leniency sparked deep controversy and debate within the United States and around the globe. Some Americans believed Calley was made a scapegoat for a systemic failure that reached to higher ranks, while others argued that his punishment was insufficient given the scale of the crime. Ultimately, the limited legal accountability for those responsible at My Lai underscored the difficulty of administering justice for wartime actions that, while clearly illegal and immoral, happened in a climate of fear, confusion, and hostility.

For the Vietnamese survivors and families of the victims, the repercussions were grievous and lasting. Beyond the immense emotional and psychological trauma, the destruction of homes, loss of family members, and disruption of community life could never be fully rectified. Some villagers left behind orphans who carried the horror of witnessing their parents, siblings, or neighbors murdered. A sense of betrayal and sorrow pervaded the area for decades, and although various reconciliation efforts have taken place, the emotional scars persist. Monuments, museums, and annual commemorations in Vietnam serve as solemn reminders of what happened, ensuring that future generations understand the tragedy of My Lai within the broader tapestry of Vietnam’s history.

In the United States, the revelation of My Lai magnified opposition to the war and prompted deeper skepticism toward government accounts of military operations. The massacre raised pressing moral questions: How could ordinary men commit such atrocities? To what extent should soldiers follow orders, especially when those orders conflict with moral principles or international law? Many pointed to factors like group mentality, fear, dehumanization of the Vietnamese, and inadequate leadership as catalysts that allowed the unthinkable to occur. Scholars and historians have since examined the massacre in the context of broader trends, including the strain of combat, the difficulties of distinguishing civilians from combatants, and the pressures to report high enemy body counts. The conversation has transformed My Lai into a case study in military ethics, emphasizing the need for rigorous training, oversight, and moral accountability within armed forces.

Over the years, My Lai has served as an important lesson about the human cost of war. It exposed the dark reality that even soldiers from nations championing liberty and human rights can commit egregious acts if left unchecked or if placed under unrelenting stress. This realization encouraged efforts to refine the U.S. military’s rules of engagement, strengthen accountability measures, and develop better channels through which service members can report misconduct. Additionally, the tragedy has fueled arguments for more robust international oversight, calling upon global leaders to ensure that such violations of human rights are investigated and punished appropriately. Although many of these changes took time and faced resistance, the My Lai Massacre acted as an inflection point that forced the U.S. military and government to confront moral responsibility on the battlefield.

Even decades later, the specter of My Lai hangs over discussions about the Vietnam War and the American involvement in foreign conflicts. For Vietnamese communities, the massacre remains a painful chapter in a much broader narrative of resistance, survival, and recovery from the ravages of war. For American veterans, and for those who lived through the tumult of the Vietnam era, My Lai represents an anguished memory of a war that divided a nation and challenged its moral foundations. Monuments, documentaries, and in-depth historical research continue to examine the events in Son My, offering an ongoing opportunity for reflection on the dangers of dehumanization, fear, and unchecked power in times of armed conflict.

The story of My Lai is ultimately a warning to future generations, a grim testament to what happens when the moral compass is lost amid the fog of war. It illustrates the devastating impact when suspicion, confusion, and hatred override basic respect for human life. Although the massacre may be a singular event in terms of its notoriety, its lessons echo far beyond 1968. Contemporary humanitarian laws, rules of engagement, and ethical frameworks in military academies and institutions often invoke My Lai as a cautionary example, reminding us that moral obligations do not dissipate under fire, and that even in war, lines must be drawn to safeguard innocent lives. By remembering and acknowledging this tragedy, society reaffirms the belief that we must hold individuals and systems accountable, strive for transparency, and preserve the dignity of all people—even in times of profound conflict.