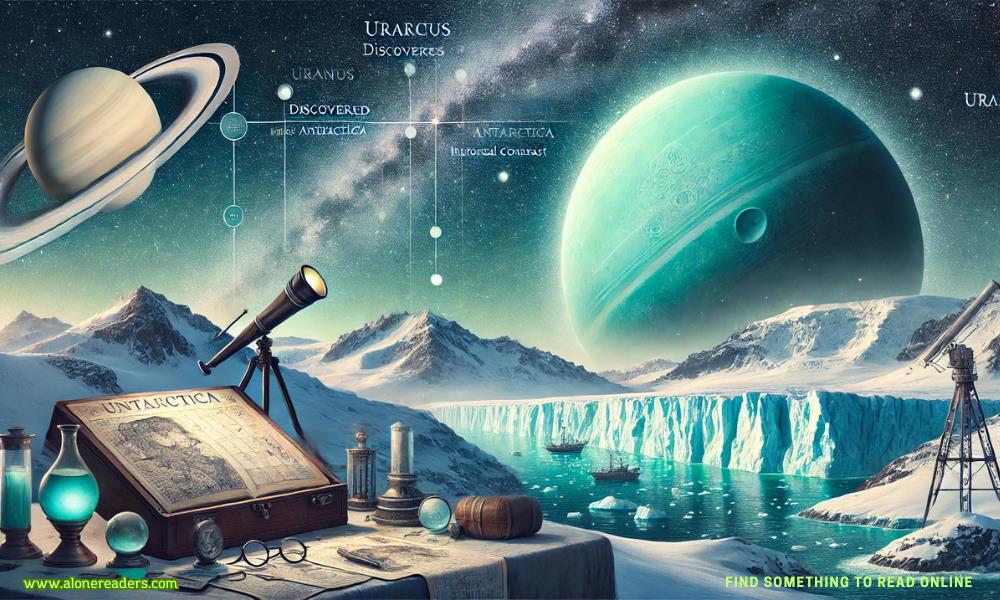

The discovery of celestial bodies and the mapping of our own planet tell a fascinating story of human curiosity, perseverance, and evolving technology. One particularly intriguing historical fact is that Uranus, a distant planet in our solar system, was discovered in 1781, decades before Antarctica—an entire continent on Earth—was officially sighted in 1820. This timeline reveals much about the priorities, challenges, and technological capabilities of the periods in question, as well as the profound differences in exploring the heavens versus our own world.

The discovery of Uranus was a watershed moment in astronomy. Until the late 18th century, the known solar system was limited to six planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. On March 13, 1781, William Herschel, a German-born British astronomer, observed Uranus through his telescope, mistaking it at first for a comet. It was only after further observations and calculations that astronomers recognized it as a new planet. This marked the first time a planet had been discovered with the aid of a telescope, expanding the boundaries of our solar system and redefining humanity’s place in the cosmos.

The discovery of Uranus demonstrated the growing sophistication of scientific instruments and the spirit of intellectual inquiry characteristic of the Enlightenment era. Herschel’s groundbreaking work showcased how advancements in optical technology enabled humanity to peer deeper into the universe than ever before. The significance of Uranus’s discovery extended beyond astronomy, symbolizing humanity’s potential to uncover the unknown through observation, calculation, and collaboration.

In stark contrast, the story of Antarctica highlights the challenges and delays in exploring Earth's remote and inhospitable regions. By the late 18th century, large portions of the globe had been mapped, and many believed that a massive southern continent existed. This idea of Terra Australis had persisted in cartographic and scientific theories for centuries, but no one had successfully reached or documented the icy continent.

The first recorded sighting of Antarctica occurred in 1820, almost 40 years after the discovery of Uranus. Multiple expeditions lay claim to this milestone, with Russian, British, and American explorers all contributing to the story. On January 27, 1820, the Russian expedition led by Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen and Mikhail Lazarev reportedly saw the Fimbul Ice Shelf, part of the Antarctic mainland. In the same year, British sealer Edward Bransfield and American sealer Nathaniel Palmer also made sightings of the continent. Despite these achievements, Antarctica remained largely uncharted and unexplored for decades due to its extreme weather conditions and logistical challenges.

The reasons behind this chronological disparity are multifaceted. For one, exploring the heavens required telescopes and mathematical insight, while exploring Antarctica demanded physical endurance, robust ships, and an ability to survive harsh climates. The vast distances of space may seem insurmountable, but the tools required to study them were relatively accessible compared to the technology needed for polar expeditions. Additionally, societal priorities played a role. The Age of Exploration, which spurred global maritime journeys, had largely waned by the 18th century, and much of the focus shifted to trade routes and colonization rather than purely scientific exploration.

Another important factor was the inherent allure of astronomy during this period. Observing and understanding celestial phenomena were seen as noble pursuits, tied to humanity's quest to comprehend the universe and its origins. Discovering Uranus captivated the imagination of scholars and laypeople alike, symbolizing a leap forward in human knowledge. Antarctica, by contrast, represented a frozen and desolate expanse that offered little immediate utility or appeal, particularly when compared to the riches and resources of more temperate regions.

Despite the initial delays, Antarctica eventually became a focal point for scientific and geopolitical interest. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw heroic expeditions to the continent, culminating in significant advancements in polar science and international collaboration. Similarly, the discovery of Uranus paved the way for further astronomical achievements, including the identification of Neptune, Pluto, and countless other celestial phenomena. Both milestones reflect the ever-evolving relationship between humanity and the unknown, whether it lies in the stars above or the uncharted lands below.

The juxtaposition of these two historical events—the discovery of Uranus and the sighting of Antarctica—serves as a reminder of the diverse paths human exploration can take. It underscores the interplay between technological capability, environmental challenges, and societal priorities in shaping the course of discovery. The fact that a planet over a billion miles away was identified decades before an entire continent on Earth highlights the unpredictability and complexity of human progress.

Today, both Uranus and Antarctica remain subjects of intense study and fascination. Uranus, with its unique axial tilt and enigmatic atmosphere, continues to intrigue astronomers, while Antarctica serves as a critical site for climate research and a symbol of international cooperation under the Antarctic Treaty. These ongoing explorations remind us that the spirit of discovery is far from extinguished and that the pursuit of knowledge—whether celestial or terrestrial—remains a defining characteristic of humanity.