In the summer of 1945, the world stood on the precipice of an unprecedented change as President Harry S. Truman faced one of the most consequential decisions in history: whether to use atomic bombs against Japan to end World War II. This momentous choice, made amidst intense global conflict and geopolitical considerations, not only brought an abrupt end to the war but also ushered in the nuclear age, fundamentally altering international relations and military strategies for decades to come.

The roots of this decision can be traced back to the early years of the war, when the United States, alarmed by the potential of Nazi Germany developing nuclear weapons, initiated the Manhattan Project. This top-secret endeavor aimed to harness atomic energy for military purposes, culminating in the successful test of the first atomic bomb in July 1945 at the Trinity site in New Mexico. As the war in Europe ended with Germany’s surrender in May 1945, the focus shifted entirely to Japan, which continued to resist despite suffering massive conventional bombings and facing a blockade that crippled its resources.

By July 1945, Japan's situation was dire, yet its leaders showed no inclination to surrender unconditionally as demanded by the Allies in the Potsdam Declaration. This impasse placed immense pressure on Truman and his advisors to find a swift and decisive means to end the conflict. The alternative strategies—such as a prolonged blockade or a full-scale invasion of the Japanese mainland—promised substantial Allied casualties, estimated in the hundreds of thousands, and an indefinite extension of the war.

Against this backdrop, the atomic bomb emerged as a compelling option. Advocates within Truman's administration, including Secretary of War Henry Stimson and key military leaders, argued that deploying the bomb would save countless American lives and compel a swift Japanese surrender. Additionally, demonstrating the power of the atomic bomb could serve as a geopolitical statement to the Soviet Union, showcasing America's newfound military dominance in the post-war world.

Truman's decision was not made lightly. The ethical implications of using such a devastating weapon against civilian populations weighed heavily on him. However, after consulting with his military and civilian advisors, and considering the projected casualties from a conventional invasion, Truman authorized the use of the atomic bomb.

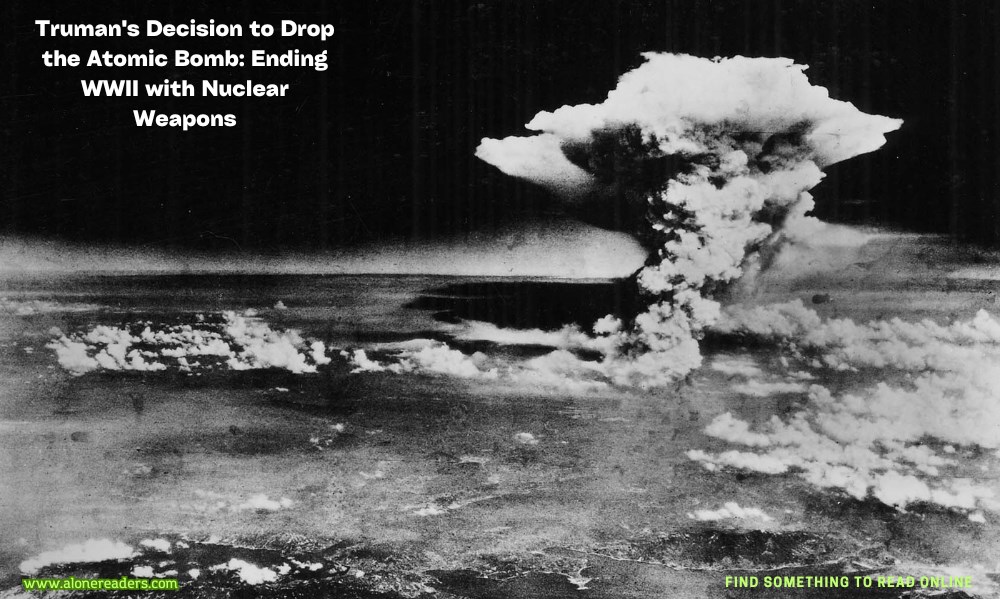

On August 6, 1945, the B-29 bomber Enola Gay dropped the first atomic bomb, codenamed "Little Boy," on the city of Hiroshima. The explosion unleashed unprecedented destruction, instantly killing an estimated 70,000 people and causing long-term radiation effects that claimed many more lives. Despite the horrific impact, Japan did not immediately surrender, prompting the United States to drop a second bomb, "Fat Man," on Nagasaki on August 9, 1945. This second attack resulted in the deaths of an additional 40,000 individuals and compounded the catastrophic effects on the civilian population.

The devastation wrought by these bombings, combined with the Soviet Union's declaration of war on Japan, finally led to Japan's surrender on August 15, 1945. World War II, the deadliest conflict in human history, was over, but the consequences of Truman's decision reverberated far beyond the immediate end of the war.

The use of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki has been a subject of intense debate and ethical scrutiny ever since. Critics argue that Japan was already on the brink of surrender and that the bombings were unnecessary acts of violence against civilians. Some historians suggest that the bombings were motivated more by a desire to intimidate the Soviet Union and establish American supremacy in the post-war order than by a need to force Japan's surrender.

Proponents, however, maintain that the bombings were a necessary evil to end the war quickly and save lives. They argue that the shock and awe of the atomic bombings hastened Japan’s surrender, preventing the much higher casualties that would have resulted from an invasion of the Japanese mainland. Moreover, the bombings exposed the horrors of nuclear warfare, leading to a global movement towards non-proliferation and eventually to international treaties aimed at controlling nuclear weapons.

In the aftermath of the bombings, Hiroshima and Nagasaki became symbols of peace and the anti-nuclear movement. Survivors, known as hibakusha, have shared their harrowing experiences, advocating for a world free of nuclear weapons. The bombings also spurred scientific and public debates about the ethics of nuclear energy and weaponry, influencing global policies and the development of international law regarding the use of such weapons.

Truman’s decision to drop the atomic bomb remains one of the most significant and controversial actions in modern history. It ended World War II, but at a tremendous human cost, and marked the beginning of the nuclear age, a period characterized by both the potential for unprecedented destruction and the pursuit of peace through deterrence. As the world continues to grapple with the legacy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the lessons of 1945 serve as a stark reminder of the devastating power of nuclear weapons and the importance of striving for a world where such weapons are never used again.